Ever since I released “The Unfinished World”, book two of “The Armor of God”, I’ve gotten a lot of messages telling me “Who do you think you are, George R.R. Martin? Get your own thing!”

I am a huge fan of Martin, “Game of Thrones”, and “A Song of Ice and Fire”, yes. And yes, way more than half the main cast is dead-for-good by the end of “The Unfinished World” but I can sincerely tell you that I don’t want to hop on the “This writer is known for killing a lot of characters” train; it’s a cheap and easy train. It takes no talent to kill characters off (though doing it “right” isn’t as easy, and that’s a whole post in itself).

The one thing for which I want to be known as a writer is not an ability to kill off characters, but an ability to execute an effective plot twist.

Well that, and a whole other gamma of things, but the writing of a plot twist is, I think, one of my strengths, and a signature in everything I’ve written, not to mention one of my favorite resources in storytelling.

So, if you’re currently writing a story that involves twists and turns, I hope reading this will help you fine tune the story for maximum effect; if not, hopefully this might inspire you to do so.

Let’s get started.

What is a plot twist?

The plot twist is one of the most important elements of storytelling. No story can go by without one, at least in its most basic sense. If you’re raising an eyebrow at this concept, let me explain: a plot twist doesn’t have to be the ending reveal where Scruff McGruff has been dead all along, or that Friendly Old Man turns out to be the villain; it’s simpler than that.

Basically, a plot twist is a point in any story which makes it take a turn that is unexpected for the characters (not necessarily the audience). It doesn’t have to be a U-turn, but it does have to change direction. Most traditionally written stories will have the mandatory twist at the end of act one, more or less one third into the plot.

One particular movie which became famous for its plot twist — which I don’t personally like — explained this basic concept in a very meta way. Halfway through “The Sixth Sense”, Bruce Willis’ character Malcolm tells Cole, a child he’s working with, a bedtime story involving characters going on a roadtrip. Cole finds it boring because nothing unexpected happens, and says: “You have to add twists and stuff. Maybe they run out of gas.”

Well, it’s that simple.

A twist, even the smallest one, one that can barely be called a twist and could more accurately be called a “development”, or a “reveal” (welcome to writing semantics 101), has to happen, or else the story will never be interesting. Here are a few examples of “detonator” twists in well-known stories.

· “The Lord of the Rings”. Frodo gets the One Ring and must set out to destroy it.

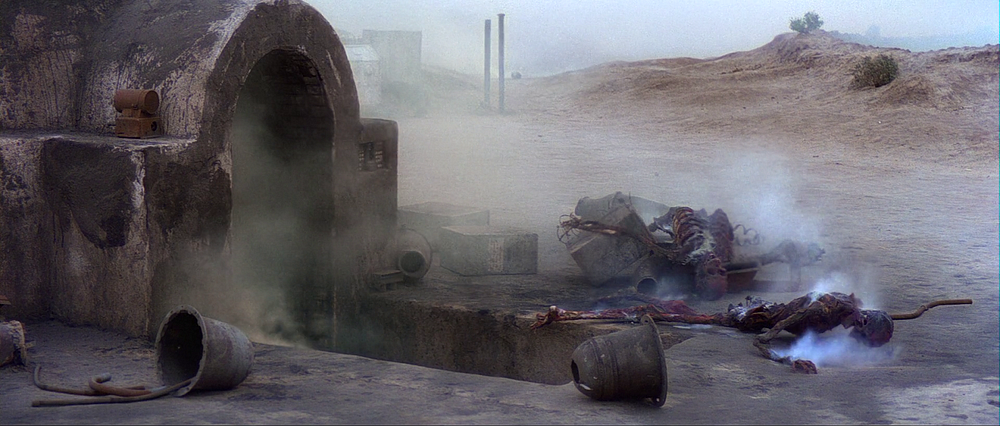

· “Star Wars”. The Empire kills Luke’s aunt and uncle and he must set out to join the rebellion.

· “Spiderman”. Peter Parker is bitten by a radioactive spider and becomes a superhero.

A plot twist must always be there to take the story in a new direction, or else we’d be stuck living with Frodo in the Shire, with Luke in Tatooine, or with Peter being a big nerd with a 100% alive uncle. Those wouldn’t be interesting stories, would they?

Did it need to be this horrifying though?

Now that we’ve established the importance of the plot twist, even the smallest, least shocking one, I can give you the first golden rule:

Not every story needs, or would benefit from, a huge twist.

As with any narrative device, you need to make sure that your story would benefit from it before forcing it in. There are few things that bother me more than stories where you can just tell that the writer came up with a twist and then wrote a story around it. The twist should be a payoff, never the focal point of the story.

Now, let’s move on to the more interesting juice.

. . . but first, try to answer the following question:

Does a plot twist have to be shocking to be good?

Knee-jerk reaction: duh, of course. Who’s ever remembered a plot twist that wasn’t shocking? Well, hold your horses and re-read the last paragraph. Here’s a truth any writer who has an interest in shocking/surprising his or her readers needs to remember:

Being shocking is only one part of a good plot twist.

Albeit, it’s probably the most important part of the twist, but not the only one. In fact, if it is the only relevant part of the plot twist, it’s not going to be a good one. A bit down the line, I’ll name a few of really famous plot twists that are known for being shocking, but, narratively, aren’t very good, and should never be emulated.

But first things first. A good plot twist has to have several characteristics to be truly great. Let’s explore this by first understanding the types of twists there are:

1) The plot twist where something unexpected happens

2) The plot twist where something unexpected is revealed

3) The plot twist that does both of the above

Both published novels in “The Armor of God” series employ all three kinds of twist. Neither one is really better than the others; you must know what kind of twist will fit your narrative best. To determine that, you should understand each one’s strengths and weaknesses. Let’s dive in.

Type 1: The One Where Something Unexpected Happens

This is a point in the story when something happens, either coming from inside the characters or outside, which redirects the story from that point on. Like we established before, this twist can have varying degrees of intensity/shock value, and can happen at any point in the story. The important part is that when this happens, everything about the story must go on a different direction. Let’s go through some examples.

· “A Game of Thrones”. Ned Stark loses his head.

· “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire”. Katniss must go back to the arena in the Quarter Quell.

· “Star Wars: The Force Awakens”. Kylo Ren kills Han Solo.

· “Game of Thrones (Season 6)”: Cersei’s trial is blown to bits.

If the story changes from the point of the twist forward, you got a type 1. This is by far the easiest twist to write because it doesn’t need as much careful planning and setup; the event happens at that moment in the plot, and the revelation will only have an effect from that point forward. These are so popular because they’re almost impossible to predict, as there can’t really be any foreshadowing. Sudden character deaths are almost always part of this type, for instance.

The difficult part here is making sure that your big shocker has consequences, or else it will diminish its narrative value.

Type 2: The One Where Something Unexpected is Revealed

I love this type of twist because it’s far trickier and, if pulled off right, will leave audiences picking pieces of their brains for the next three days.

This type of plot twist makes a sneaky revelation that will shock the audience and change everything they thought they knew about the story completely, from that point back, as opposed to type 1, which changes the story from that point forward. This type of twist retro-actively affects the story and characters.

In other words, this is the type of twist that makes you go “Oh shit, so that’s why [blank]!”

Some examples.

· “Silent Hill 2”. James killed Mary three years ago.

· “The Maze Runner”. The word “rescue” is put in quotation marks in the final report.

· “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows”. Harry is a Horcrux.

· “Zombieland”. Tallahassee’s “puppy” was his son.

· “Soylent Green” . . . is people!

These twists aren’t necessarily revealed during momentous events. Nothing big has to happen for it to be effective (though it can work in its favor if it does). Something big is revealed instead. Like I said, this one is way trickier to write, as it requires a lot of careful planning, red herrings, misdirection, and similar tactics to pull off. Writers like JK Rowling and Dan Brown love type 2s.

Type 3: The One That Does Both

The best type of twist is the one where both of these things happen at once; they both change everything you knew about the story, and everything you imagined the story would become.

· “The Empire Strikes Back”. Darth Vader is Luke’s father.

· “A Storm of Swords”. A massive coup is carried out against the Stark army during a wedding.

· “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire”. The Tournament was rigged to bring Voldemort back.

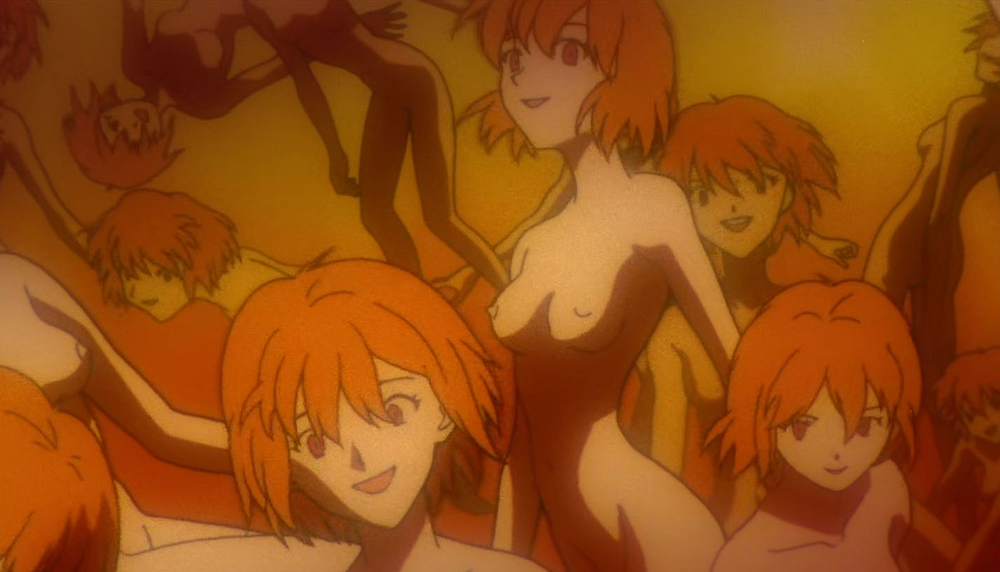

· “Neon Genesis Evangelion”. There are hundreds of Reis, and Shinji has met three.

· “The Others”. The characters you thought were ghosts were alive…and viceversa.

These are twists that make you go “Oh, so that’s why [blank]! And now, holy shit, [blank]!”

These have all the strengths and weaknesses of both types, and can both be effective as hell (The Red Wedding) or total duds (surprise villain revelations, most commonly).

So what makes a good plot twist?

For a plot twist to be good, it should cover most of the following characteristics, which I’m listing in order of importance.

· It has to be surprising

· It has to deeply affect the story and the characters

· It has to be narratively sound and perfectly gel with the established story

· It has to be foreshadowed (if possible), maybe even anticipable

· It must be shown, not told

Ideally, a plot twist should put check marks on all five of these, though the last two aren’t mandatory.

Now, reader, think of your favorite plot twist, or the most memorable you’ve seen. Think of the ones you’ve written and the ones you intend to write. In what category do they fit? Do they cover all five characteristics?

Twisting 101

Here are some tips to make the best out of your plot twists.

1. The Foreshadowing

If you have a Type 2 or 3 twist, then you need to take into account that it needs to be happening in your story from the beginning. How is the hidden plotline coming into play in your non-hidden plotline? Your twist needs to poke its ugly head out every once in a while in any way it can.

This is what’s tricky, because you can never straight up lie to your audience. You can lie to your characters and misdirect your audience, but never lie to your audience directly. And at the same time, you can’t make the foreshadowing too obvious without giving it away too early.

The trick is to always know where your audience stands in terms of story appreciation and understanding. This is tougher than it sounds because you need to keep track of every single revelation, no matter how minute, you’ve made at any given moment in your story. You need to know exactly what your reader knows at any given moment, you need to keep track of any red herrings you’ve done, of any meta-narrative you’ve added, etc.

Sometimes, a good thing to do if you can’t do it all in your head is to open up a Word document and make a list of every twist and development, and then break each down to their smallest appearance in the story. Once you have this longer list of every small revelation, you write down at what point in your story each revealed, and how/by whom.

2. The Big Reveal

To no one’s surprise (no pun intended ) this one’s the hardest aspect to really pull off because it’s completely dependent on the story, and on another layer, completely dependent on the reader.

But there is at least one thing you can do to have the best chance at a big shock, and that’s in the reveal.

Answer this question: How does the character/s find out what the twist is about? Do they discover it themselves or are they told by someone else? Usually, the best way to make a reveal is to make it fit the context of the twist, and to have the character/s immediately appreciate the scale of what has happened or what has been revealed.

If the character can appreciate this, so will the reader.

The best twists are discovered, not spoken. This is what the whole “show, don’t tell” is talking about.

My favorite example of a powerful reveal is “The Red Wedding” from “Game of Thrones” (and obviously “A Storm of Swords”), probably one of the most shocking and well executed twists in modern fiction. You can go through that scene and notice how it builds small reveal over small reveal to make it worse until wham. Here’s the scene:

The devices used leading to the massacre were the following:

· Roose Bolton isn’t drinking at the wedding.

· The great doors of the hall are closed.

· “The Rains of Castamere” begins playing.

· The soldier outside claims that “the wedding is over” when we know it’s not.

· Catelyn uncovers Roose’s chain mail.

Notice anything here? Not one of these devices would mean anything by themselves, but one after the other give a great effect of build-up in just a few seconds/pages because we begin putting two and two together, and it gives a feeling of impending doom. Of course this one also goes way further because the shock isn’t only the revelation of the betrayal, but how far the author takes that betrayal — to the deaths of three of the main “good guy” characters, ending any chance of our favorite family winning the war.

Analyze this scene to see how to pull off an effective reveal and see if your favorite movie twists can be compared, and how would they compare.

3. The Aftertaste

Ideally, the shock shouldn’t end on the reveal itself. To have an even better effect, you need to force your reader, if not your character, make a bunch of connections in his head. Things need to begin adding up in a way that they feel stupid for not seeing it coming. That’s what the foreshadowing is for.

Of course, as we saw earlier, not every type of twist can be seen coming. Only Type 2s and 3s.

You need to do your best to make sure your reader says the ever satisfying “Oh, so that’s why…”

· “Oh, so that’s why Harry could speak in Parseltongue.”

· “Oh, so that’s why Vader didn’t kill Luke.”

· “Oh, so that’s why Rei kept miraculously surviving huge explosions.”

· “Oh, so that’s why Esther the orphan was so smart and manipulative.”

Examples of Shocking Twists (Which Were Terrible)

As I said before, there are many writers, or movies, or stories, that have become famous for having shocking plot twists. I’ve always been on a crusade against a lot of them because I hate a twist that’s shocking for the sake of being shocking. I hate it because it’s cheap, easy writing. Some examples of these surprising though narratively poor twists:

· “SAW”. Jigsaw is the guy in the room, not the one outside. I don’t even know where to start with this one; not only did it serve no purpose to the story and could’ve been removed entirely, but it also fails to gel coherently with what’s supposed to have been happening. It’s a disaster and it boils my blood when I think of how many people wanted to emulate it.

· “The Village”. The story is set in modern times, not the 19th century. The shock is 100% dependent on its marketing; the character doesn’t know what “modern times” is.

· “Broken Age”. Shay’s spaceship is the monster in Vella’s story. The shock is 100% dependent on the game being told through two characters’ POV. If you had only followed one character’s story, the twist wouldn’t exist.

· “Final Destination 5”. Sam and Molly’s flight is Voleé Air 180. The shock is 100% dependent on the first movie existing. As much as I love this movie, and how well it was hidden, this twist was just fan service.

These are twists that were written with the sole intention of shocking the audience by changing everything we thought we knew, but without affecting the characters in any significant way.

There are other ways an unnecessary or poorly executed twist will mess up your story, which is why you always need to make sure from the very beginning that the twist fits. Never let your twist make the house of cards that is your story fall apart because you were more interested in shocking your audience than in giving them a good story.

Conclusion

I think a rule to help avoid messing up your narrative to put in a twist is the following:

A good plot twist should build upon the central concepts, and never replace or contradict them.

This applies not only for the big payoff, but for any plot development. Think of what the central concept of the plot is, and try to understand how this development builds upon it.

To understand this better, I recommend you read, if you haven’t, a short Japanese horror comic called “The Enigma of the Amigara Fault”, by horror mastermind Junji Ito.

This is one of my favorite short stories of all time, and a masterclass in building up on a central concept one step at a time for a continuous string of horrifying payoffs. I could write a whole book dedicated to how well the story does this, but if you read carefully and analyze its storytelling, you’ll notice how every page adds a small layer to the central idea (which is “there are people-shaped holes in the mountain”). There are at least eight important plot twists in this 20-page story, and not a single one that isn’t taking this idea and making it a little bit more horrifying until it ends with a one-two punch to the nads. I do intend to dissect this story for its narrative value but I will dedicate a post to it. For now, I do recommend reading it and seeing what you can draw from it. Here’s the link. It’ll take you five minutes (remember to read from right to left, top to bottom).

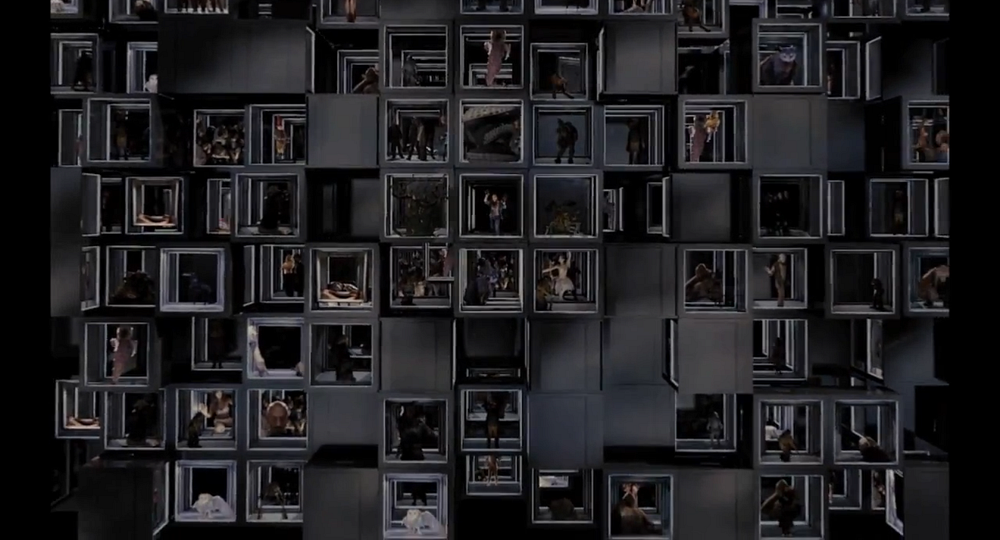

Another great example of building upon a central concept in long-form fiction is “The Cabin in the Woods”. This story will build upon itself, changing everything you thought you knew every other scene, never betraying its original idea, and, well, doing a whole other bunch of extremely special things on the way. It’s another story that can be dissected layer by layer.

Well, I’m looking at the word count in this document and it’s gone for at least twice as long as I wanted it to be.

If you enjoyed reading this, I encourage you to see these principles put into practice (or attempted) in my book series “The Armor of God”.

Remember to follow me on Twitter and Facebook for more similar content, and don’t forget to leave a comment if you agree or disagree.

Thanks for reading! See you around and good writing!